Expo

view channel

view channel

view channel

view channel

view channel

view channel

Radiography

UltrasoundNuclear MedicineGeneral/Advanced ImagingImaging ITIndustry News

Events

- AI Detects Early Signs of Aging from Chest X-Rays

- X-Ray Breakthrough Captures Three Image-Contrast Types in Single Shot

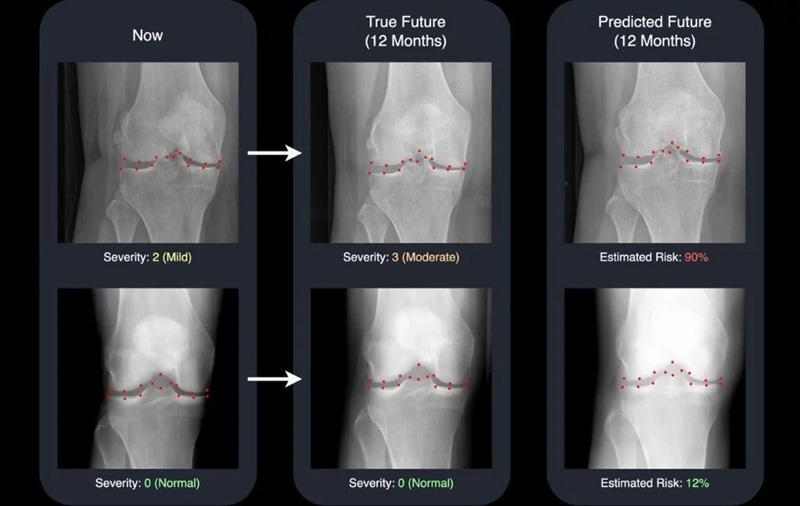

- AI Generates Future Knee X-Rays to Predict Osteoarthritis Progression Risk

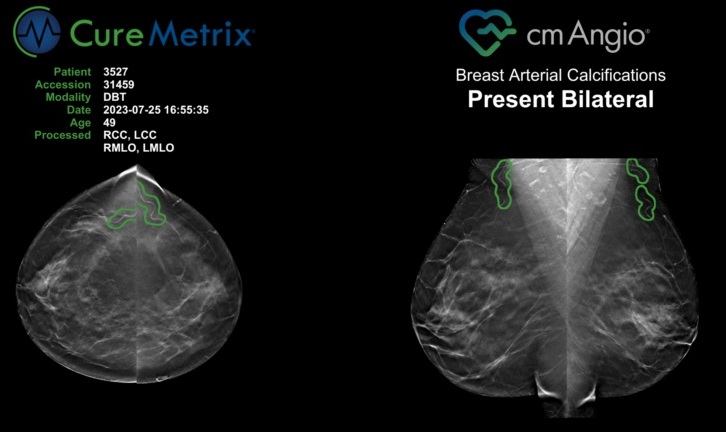

- AI Algorithm Uses Mammograms to Accurately Predict Cardiovascular Risk in Women

- AI Hybrid Strategy Improves Mammogram Interpretation

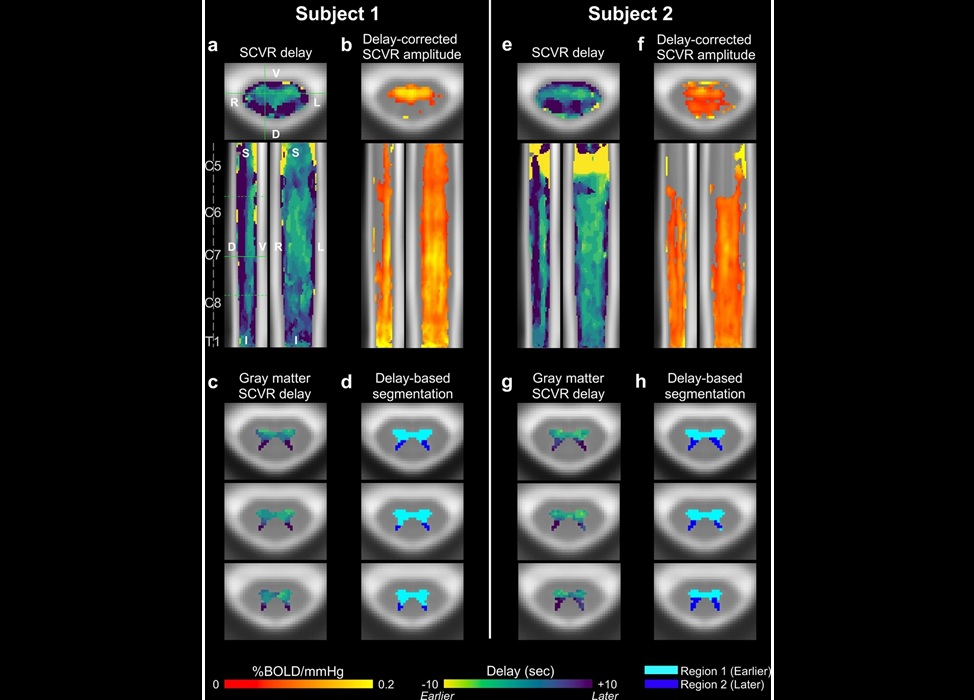

- Novel Imaging Approach to Improve Treatment for Spinal Cord Injuries

- AI-Assisted Model Enhances MRI Heart Scans

- AI Model Outperforms Doctors at Identifying Patients Most At-Risk of Cardiac Arrest

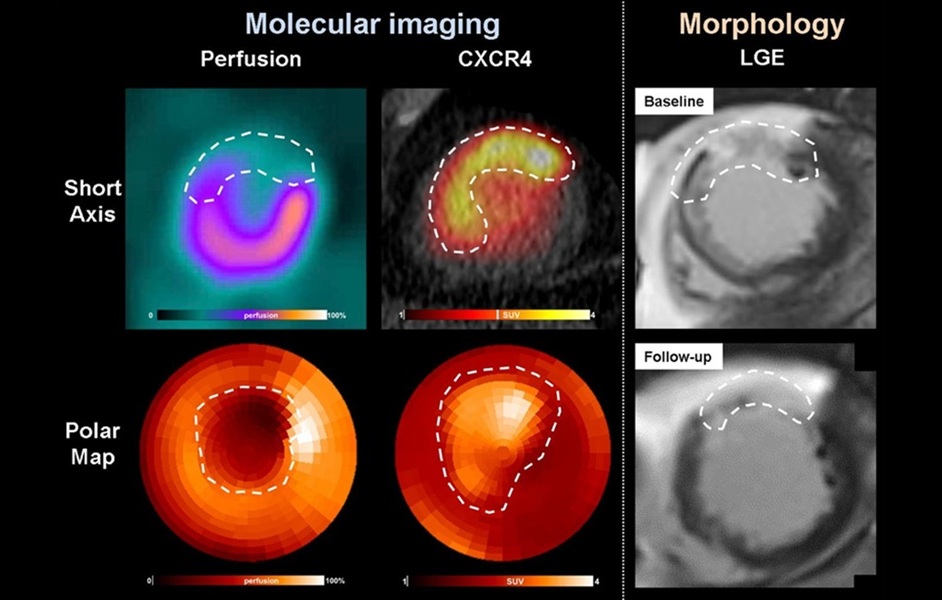

- New MRI Technique Reveals Hidden Heart Issues

- Shorter MRI Exam Effectively Detects Cancer in Dense Breasts

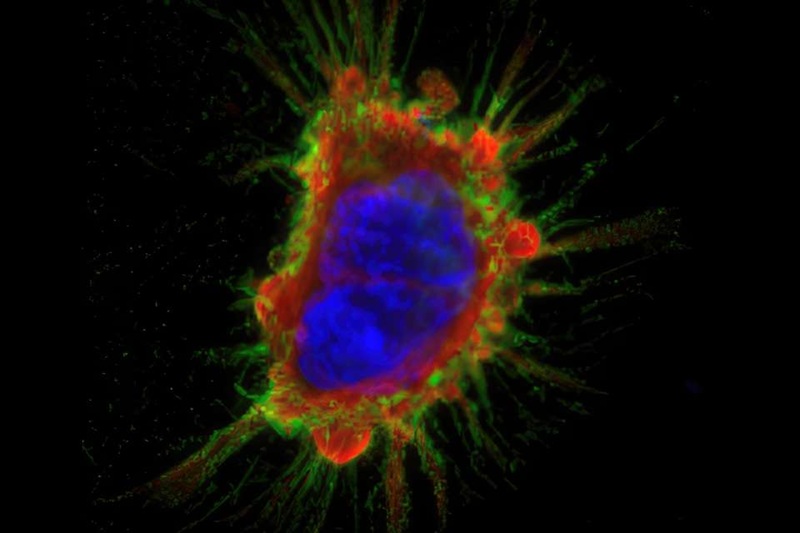

- Radiotheranostic Approach Detects, Kills and Reprograms Aggressive Cancers

- New Imaging Solution Improves Survival for Patients with Recurring Prostate Cancer

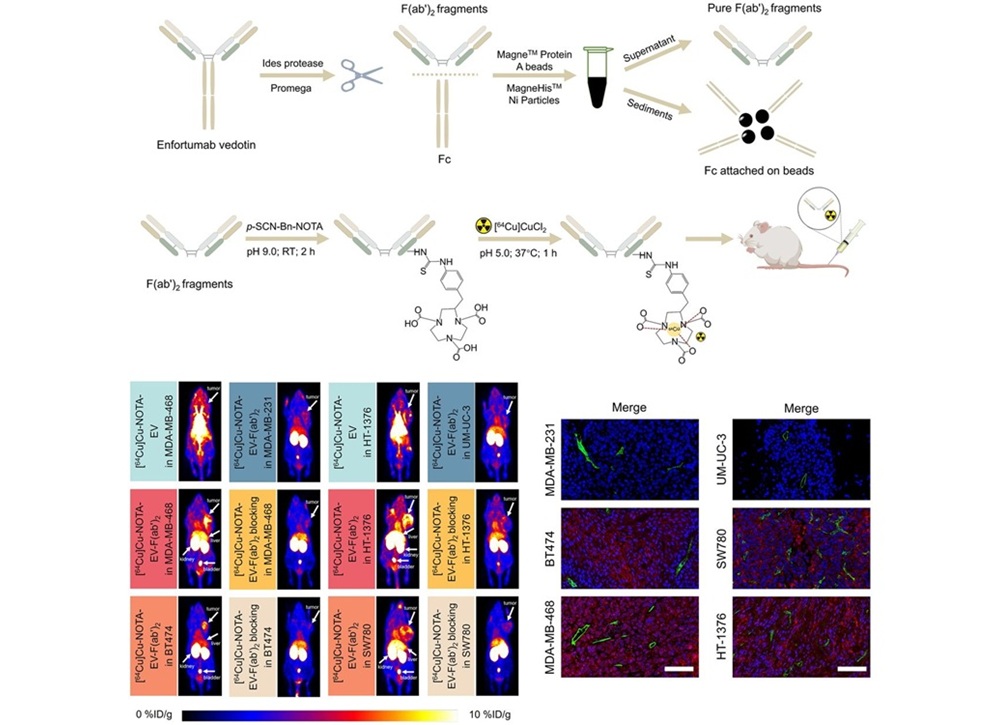

- PET Tracer Enables Same-Day Imaging of Triple-Negative Breast and Urothelial Cancers

- New Camera Sees Inside Human Body for Enhanced Scanning and Diagnosis

- Novel Bacteria-Specific PET Imaging Approach Detects Hard-To-Diagnose Lung Infections

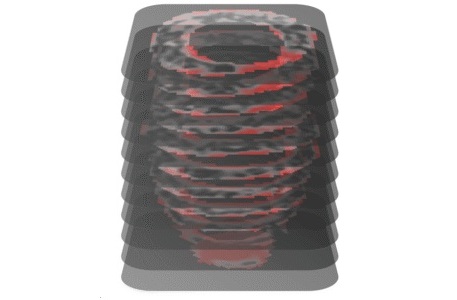

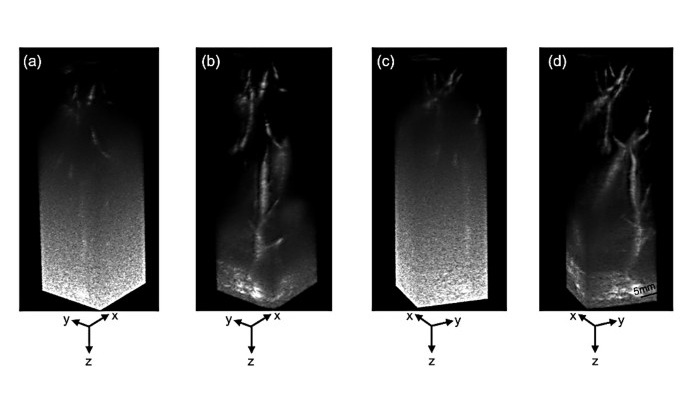

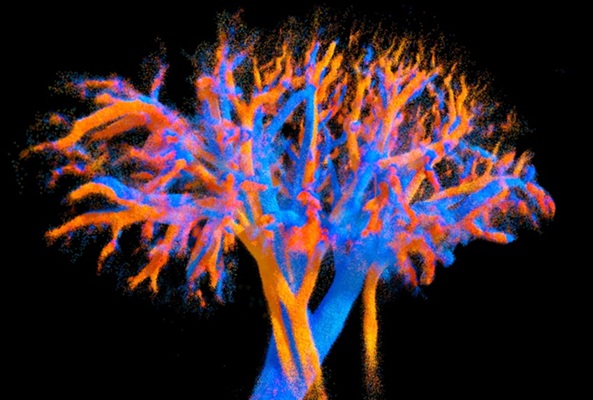

- Ultrasound Technique Visualizes Deep Blood Vessels in 3D Without Contrast Agents

- Ultrasound Probe Images Entire Organ in 4D

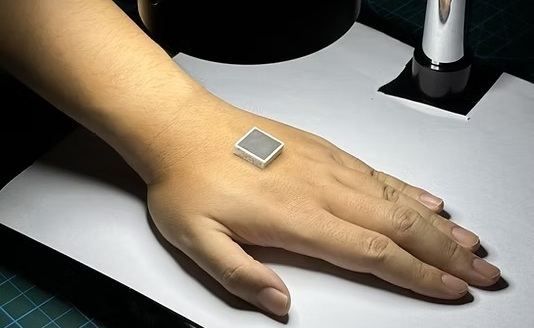

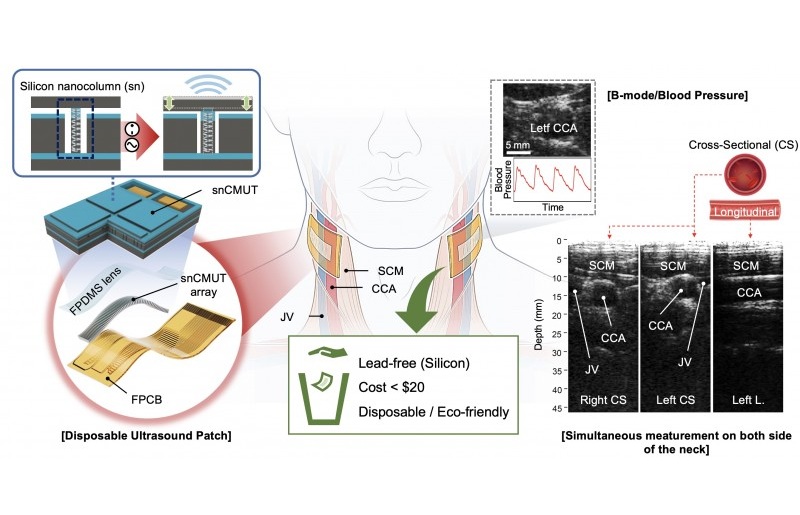

- Disposable Ultrasound Patch Performs Better Than Existing Devices

- Non-Invasive Ultrasound-Based Tool Accurately Detects Infant Meningitis

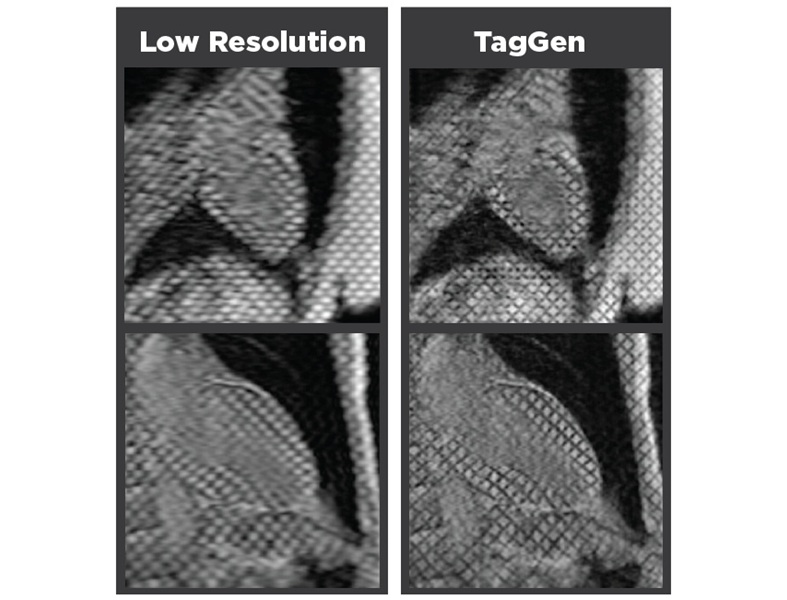

- Breakthrough Deep Learning Model Enhances Handheld 3D Medical Imaging

- Global AI in Medical Diagnostics Market to Be Driven by Demand for Image Recognition in Radiology

- AI-Based Mammography Triage Software Helps Dramatically Improve Interpretation Process

- Artificial Intelligence (AI) Program Accurately Predicts Lung Cancer Risk from CT Images

- Image Management Platform Streamlines Treatment Plans

- AI Technology for Detecting Breast Cancer Receives CE Mark Approval

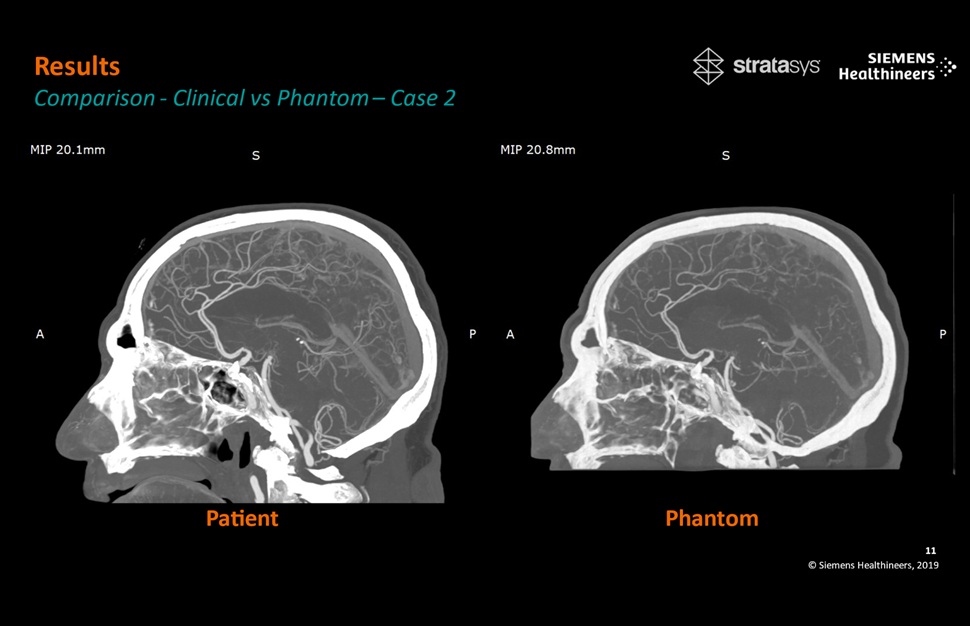

- Patient-Specific 3D-Printed Phantoms Transform CT Imaging

- Siemens and Sectra Collaborate on Enhancing Radiology Workflows

- Bracco Diagnostics and ColoWatch Partner to Expand Availability CRC Screening Tests Using Virtual Colonoscopy

- Mindray Partners with TeleRay to Streamline Ultrasound Delivery

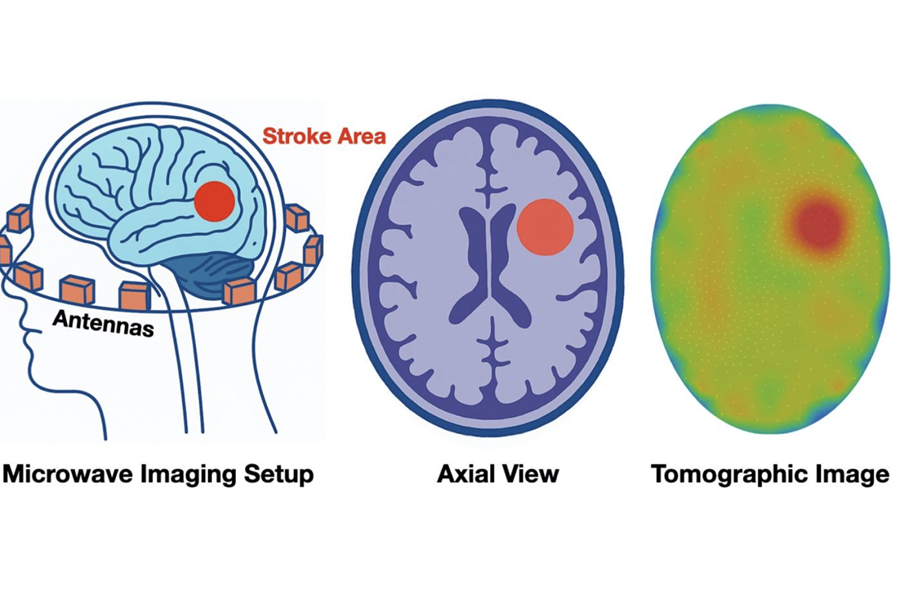

- Philips and Medtronic Partner on Stroke Care

Expo

Expo

- AI Detects Early Signs of Aging from Chest X-Rays

- X-Ray Breakthrough Captures Three Image-Contrast Types in Single Shot

- AI Generates Future Knee X-Rays to Predict Osteoarthritis Progression Risk

- AI Algorithm Uses Mammograms to Accurately Predict Cardiovascular Risk in Women

- AI Hybrid Strategy Improves Mammogram Interpretation

- Novel Imaging Approach to Improve Treatment for Spinal Cord Injuries

- AI-Assisted Model Enhances MRI Heart Scans

- AI Model Outperforms Doctors at Identifying Patients Most At-Risk of Cardiac Arrest

- New MRI Technique Reveals Hidden Heart Issues

- Shorter MRI Exam Effectively Detects Cancer in Dense Breasts

- Radiotheranostic Approach Detects, Kills and Reprograms Aggressive Cancers

- New Imaging Solution Improves Survival for Patients with Recurring Prostate Cancer

- PET Tracer Enables Same-Day Imaging of Triple-Negative Breast and Urothelial Cancers

- New Camera Sees Inside Human Body for Enhanced Scanning and Diagnosis

- Novel Bacteria-Specific PET Imaging Approach Detects Hard-To-Diagnose Lung Infections

- Ultrasound Technique Visualizes Deep Blood Vessels in 3D Without Contrast Agents

- Ultrasound Probe Images Entire Organ in 4D

- Disposable Ultrasound Patch Performs Better Than Existing Devices

- Non-Invasive Ultrasound-Based Tool Accurately Detects Infant Meningitis

- Breakthrough Deep Learning Model Enhances Handheld 3D Medical Imaging

- Global AI in Medical Diagnostics Market to Be Driven by Demand for Image Recognition in Radiology

- AI-Based Mammography Triage Software Helps Dramatically Improve Interpretation Process

- Artificial Intelligence (AI) Program Accurately Predicts Lung Cancer Risk from CT Images

- Image Management Platform Streamlines Treatment Plans

- AI Technology for Detecting Breast Cancer Receives CE Mark Approval

- Patient-Specific 3D-Printed Phantoms Transform CT Imaging

- Siemens and Sectra Collaborate on Enhancing Radiology Workflows

- Bracco Diagnostics and ColoWatch Partner to Expand Availability CRC Screening Tests Using Virtual Colonoscopy

- Mindray Partners with TeleRay to Streamline Ultrasound Delivery

- Philips and Medtronic Partner on Stroke Care